In an age of advancing health care and medical technologies, is the threat of an Ebola outbreak a concern for the US?

In an age of advancing health care and medical technologies, is the threat of an Ebola outbreak a concern for the US?

By Diane Atwood ’77

Ordinarily, in the spring a group of Saint Joseph’s College nursing students and a clinical faculty member travel to Senegal, West Africa. “We take them to various parts of the world,” says professor of nursing Sharon Martin, PhD, MSN, RN. “It’s an important part of understanding world health and working with people from other cultures.”

But this past spring, circumstances in West Africa were anything but ordinary. By the end of March 2014, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia were in the grips of an Ebola outbreak. Although at the time no cases had been reported in Senegal, the risk was too great and the trip was cancelled. “I couldn’t guarantee that it wouldn’t get into Senegal,” says Martin. “I knew way back in the spring from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that it probably wouldn’t be until December that they got it under control.”

It now appears that it will take longer than predicted. The Ebola outbreak has evolved into one of the largest in history, killing more people than all previous outbreaks combined. By late July it had spread into Nigeria, and on August 29, Senegal reported its first case. An outbreak in The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was reportedly not connected to the larger outbreak.

As of January 16, 2015, a total of 13,477 laboratory-confirmed cases had been reported, and 8,468 people have died. In early September, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, said the epidemic was spiraling out of control. At a CDC briefing, he said, “This is not just a problem for West Africa, not just a problem for Africa. It’s a problem for the world, and the world needs to respond.”

Global Concern

International travel is one of the major reasons for a resurgence of many infectious diseases in the United States over the past two decades. “In just a matter of hours, one can get on a plane and be across the world, even in a remote part of the world,” says Mary McFadden ’02, RN, MHA, CIC, CHS, director of infection prevention at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC.

“Is it possible for us to get a case in the United States? Sure,” says McFadden, “but it’s not as truly transmissible as one would think. If you just traveled to Liberia, that is not considered an exposure. You have to come into direct contact with the blood or body fluids of someone who is actively infected.”

A major problem in Africa is the lack of a robust health care infrastructure. “They’re taking care of patients in huts out in fields or in crowded buildings where they’re lined up one after the other,” McFadden says. “There’s a lot of exposure because they don’t have the correct type of facility or even enough of the personal protective equipment we have in the United States, so the spread is that much more magnanimous.”

“They also have to make do with minimal supplies, minimal water for washing, minimal hand solutions,” says Martin. “And there are so few health care providers and so many people sick that it’s just ripe for error.”

Signs of Hope?

Ebola is a horrific disease with no vaccine and no cure. The first human trial for a vaccine began the first week of September 2014. The experimental drug ZMapp, which was given to two infected American aid workers, is designed to treat rather than prevent Ebola. “The drug was offered to the two by the manufacturer,” says McFadden when asked about using ZMapp in Africa. “It is not approved by the FDA, and the FDA would never approve a drug like that for use with mass casualties when it’s only been tested on animals. There’s so much more testing that they have to go through.”

The fact that the Ebola virus currently kills about half the people it infects creates panic among some people, even when their personal risk is almost nil. A recently released poll of 1,025 adults by the Harvard School of Public Health shows that roughly four in 10 (39 percent) adults in the US are concerned that there will be a large outbreak in this country, and more than a quarter (26 percent) are concerned that they or someone in their immediate family may get sick with Ebola over the next year.

There is no denying it. We live in a contagious world and many infectious diseases are scary. Scientists and health care professionals across the planet are working tirelessly to improve disease surveillance, strengthen public health infrastructure, and develop effective prevention and treatment protocols.

What can the rest of us do? “Wash your hands often, cover your nose and mouth when you cough or sneeze, and stay home when you’re sick,” recommends Martin. “Other than that, live your life.”

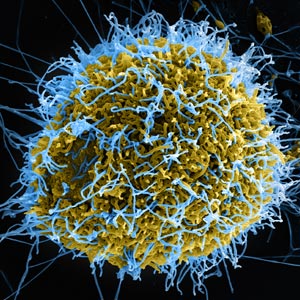

Portrait of a Virus

Ebola is a virus that is carried by animals—the lead suspect in the current outbreak is a fruit bat. The virus is transmitted to humans through direct contact with an infected animal’s blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids. The same is true for human-to-human transmission. The CDC estimates that approximately 75 percent of newly emerging infections are transmitted from animals to humans.

Smallpox killed between 300 and 500 million people in the 20th century before it was eradicated in 1980, a feat accomplished by tracking down people who had been exposed to the disease and vaccinating them as quickly as possible.

The first vaccine for a virus was created in 1796. It targeted smallpox.

In 2009, H1N1 influenza, referred to as swine flu, spread to more than 213 countries and caused the first declared pandemic of the 21st century. New strains of influenza frequently occur, which is why seasonal flu vaccine usually changes every year. But in 2009, the strains had already been chosen and didn’t include H1N1. A separate vaccine had to be created.

Diane Atwood ’77 writes the award-winning health and wellness blog Catching Health with Diane Atwood. She was a longtime health reporter on WCSH-TV, and now appears as a regular guest on the station’s “Morning Report.”

Photo by Creative Common